Will the North Atlantic Right Whale Become Extinct Under Our Watch?

Despite presidential executive orders, five offshore wind areas are under construction off the East Coast. Meanwhile, concerns about sonar and strandings were deleted from a federal agency website.

The death of a giant tortoise in 2012 was a heartbreaking story told around the world.

Aptly named Lonesome George, he was the last known creature of his species. And when he died the Pinta Island tortoise “passed into the timeless, they can never more be found.” *

Unlike mass extinction events that shaped the Earth many millions of years ago, what researchers call today’s “extinction crisis” is one entirely created by us. A 2023 study found that if over half of the known endangered species are to avoid “human-induced extinction” it will require “targeted recovery actions.”

One of those gravely endangered species is the North Atlantic right whale, which is fast approaching the tipping point of extinction. While this magnificent marine mammal may no longer face the threat of being exterminated for its oil, that doesn’t mean it won’t once again end up being sacrificed in the name of providing “power” to our homes.

‘Give right whales space’

There is no disagreement that the North Atlantic right whale is “critically endangered.” Current counts place its dwindling population numbers at a shocking 340 individuals with just 70 known reproductively active females.

There is also no disagreement that right whales have a well-established migration path along the Atlantic Coast, traveling over 1,000 miles in spring to northern feeding grounds in New England and Canada, and in the fall to birthing areas in shallower waters off Florida and Georgia. (More on a plan to protect that route in a minute.)

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – a.k.a. NOAA Fisheries -- in a 2020 news release emphasized the urgency of giving the NARW “space.” It is “extremely important for people to be aware of the whales’ movement and migratory patterns,” the agency warned, referencing dangers from vessels, drones, and even paddleboards. “Any disturbance,” it said, “could affect behaviors critical to the health and survival of the species."

Mysteriously, however, erecting hundreds of mammoth offshore wind turbines, planned to run directly through its migration path, along with all the upheaval that accompanies the construction process, wasn’t mentioned.

Why did the Marine Mammal Commission delete its concerns about sonar and strandings?

Since 2016 the federal watchdog agency known as the Marine Mammal Commission has warned that sonar surveys used to map the seafloor “can generate sound that may affect a marine mammal’s behavior,” leading to “serious consequences,” such as “stranding.”

But that concern, which appeared on its page titled “Renewable energy development and marine mammals,” is no longer there. Research at the web archives “wayback machine” discovered the reference to sonar and stranding, which was on the page for over seven years, was removed in May of 2023.

The removal coincided with the public being horrified by many dozens of marine mammal strandings along the East Coast – with 41 off the New Jersey shore from Dec. 2022 to April of 2023 alone, leading to questions about whether ongoing sonar surveys were the cause.

It was also the beginning of an all-hands-on-deck approach to label any concern about offshore wind development harming marine mammals a “debunked claim” (something still going on).

Also removed from the same page was a section and research link telling how construction pile driving “can generate sound that is detectable up to 40 km (25 miles) from the source.”

But, along with sanitizing the page to delete any mention of these dangers, something new was added — namely, a Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) fact sheet saying that BOEM and NOAA Fisheries have examined the “potential effects” of such high-resolution geophysical surveys and concluded that “these types of surveys are not likely to injure whales or other endangered species.”

(Marine Mammal Commission members are appointed after “consultation with the Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the Director of the National Science Foundation, and the Chair of the National Academy of Sciences.”)

And despite what’s been called the “Trumpian chill,” the January presidential Executive Order calling off the previous push for offshore wind, the East Coast is still facing a real and present threat from five ongoing projects as well as numerous active leases lying in wait.

No safe path

At the end of March, the New Jersey-based group Save LBI (Long Beach Island) filed a petition with BOEM and other relevant agencies asking that a safe migration corridor be established for NARW that would “prohibit offshore wind development within the proposed protected zone…”

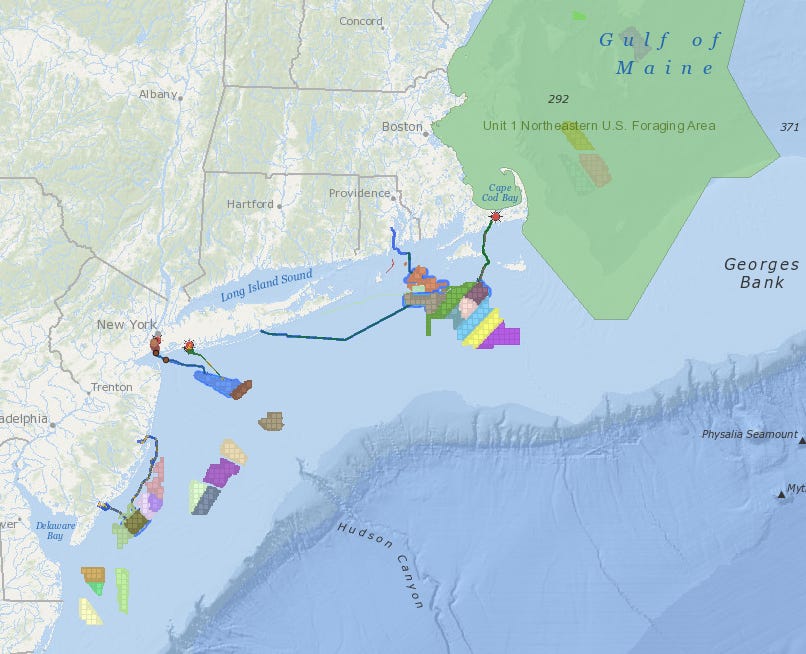

There are currently two officially designated “critical habitats” for the NARW created by NOAA Fisheries over 30 years ago -- one encompassing areas in the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank called Unit 1, the “foraging area,” and another called Unit 2, that goes from Cape Fear, N.C. to Cape Canaveral, Florida known as the “calving area.”

The missing link, according to Save LBI, is an additional critical habitat designation that would allow these whales to migrate from the calving area to foraging zones without going through a minefield of offshore wind turbines.

“Restricting the development of offshore wind projects in the migration path of the North Atlantic right whale is crucial to preventing its extinction,” Save LBI President Bob Stern, said in a statement.

“Our petition defines the whale’s primary historic migration corridor and presents calculations showing how operational noise from the numerous proposed offshore wind turbine complexes will at a minimum seriously impair and potentially block its annual migration,” Stern said. (For more about operation noise, including several audio files, see What Will 357 Wind Turbines Operating off the New Jersey Coast Sound Like?)

The group has also petitioned for the cancellation of wind energy leases (whether fully permitted or not) within the proposed migration habitat, a pause of all activities related to offshore wind development pending a decision on the petition, and a suspension of all sonar surveys during the NARW migration season.

The concept of a “critical habitat” falls under the Endangered Species Act. The unique aspect of such a designation is that, as described by NOAA Fisheries, “the only direct regulatory effect” is to not destroy or adversely modify the habitat for the listed species by any federal agency action. In other words, a critical habitat area cannot be trashed by the actions of the federal government. It’s a “regulatory tool” for managing federal activities and not a closed area.

Habitat destroyed

At the end of March, sei, fin, and humpback whales, as well as several right whales were spotted off the New Jersey coast traveling directly through the offshore wind lease area known as Atlantic Shores.

That planned project, which called for up to 200 enormous offshore turbines spanning the coast from Barnegat Light on Long Beach Island to Atlantic City, recently lost its Clean Air Act permit that was issued last year, meaning it is no longer fully permitted and unable to start construction.

Other projects, however, are. And they are doing so quickly and covertly, with minimal if any publicity.

In preparation for pounding giant 180-foot steel monopiles into the seabed, supposedly scheduled to begin in May, billions of pounds of rocks have been dropped into the water to begin the Empire Wind 1 project, positioned in waters off New Jersey and New York.

According to a recent op-ed in the New York Post by Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association, the rock dump is just the beginning of the destruction Empire Wind 1 will bring to fisheries up and down the coast.

The rocks, “…will destroy habitat, burying vital sand shoals that serve as spawning and nursery grounds for fish species like fluke, squid and scallops,” Brady said.

Other offshore wind areas currently under construction include:

Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind off Virginia Beach, which just completed the installation of the first of three offshore substations;

Vineyard Wind 1, located south of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, Mass.;

Revolution Wind, southeast of Point Judith, R.I., and

Sunrise Wind, which covers 86 thousand acres of seabed stretching from 30 miles east of Montauk, N.Y. to 19 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard.

All of these projects obstruct the known migration path of the NARW, with Vineyard and Revolution Wind forming a kind of blockade of one of the coastal sides of critical habitat Unit 1.

North Atlantic right whales have long been studied, with reams of data analyzed by conservation biologists, federal agencies, and even a dedicated consortium of experts around the globe. Many are named, identified by the unique patches of “callosities” on their heads. There is even a catalog, filled with photos of sightings going back 90 years.

But one of the most logical conservation methods would be to let them freely roam in their native habitat without placing hundreds of 850-foot-tall spinning barriers in their path.

*Dan Fogelberg, “A Cry in the Forest”

Thank you so much for this important article. It's been frustrating to see well-meaning people passing along misinformation about this subject. Of course industrial development is going to adversely affect habitat and the species who call it home; that's how it goes. Nothing "green" about extinction.

Linda: Thank you for describing BOEM/NOAA's crimes objectively and with such clarity